|

July 2013

|

Weather or Not: Why We Need to Prepare for The Worst Storms Now

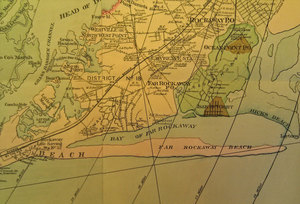

It’s not a stretch to say that most of us would prefer the 2013 hurricane season to keep to the Andrea model. The first-named storm in a season that NOAA predicts could have 20 named storms and six Category 3 hurricanes barreled through overnight in early June, leaving our lawns green, our streets washed and the sky cleared by mid-day as it headed out to sea as a fish storm. But even the fish have a message to tell us this year—the oceans are so much warmer that our aquatic food supply has headed into the colder depths, a condition that presaged the season of "The Perfect Storm" of 1991 that flooded Lower Manhattan and devastated New England. It’s not a stretch to say that most of us would prefer the 2013 hurricane season to keep to the Andrea model. The first-named storm in a season that NOAA predicts could have 20 named storms and six Category 3 hurricanes barreled through overnight in early June, leaving our lawns green, our streets washed and the sky cleared by mid-day as it headed out to sea as a fish storm. But even the fish have a message to tell us this year—the oceans are so much warmer that our aquatic food supply has headed into the colder depths, a condition that presaged the season of "The Perfect Storm" of 1991 that flooded Lower Manhattan and devastated New England.It is understandable that New Yorkers are storm-weary after three 100-year events in the last 18 months: 2011’s earthquake, tornadoes in the Bronx and Brooklyn, and Tropical Storm Irene; and 2012’s Superstorm Sandy. But Irene and Sandy lost hurricane strength immediately before or after landfall to the east and south of Manhattan, and NOAA and the National Weather Service have not officially recorded a hurricane making landfall and retaining hurricane characteristics in the five boroughs for years. (See sidebar "The Island That Disappeared" below.) Just as the reality of 9/11 changed the way our industry approaches the threat of terrorism, the new weather paradigm places storm damage prevention and mitigation at the center of our operational radars today. NYC--#2 on the "Worst" List Weather is our most costly expense, and New York City is ranked by several insurance industry analysts as No. 2 on the "worst places for a hurricane to strike" list. Miami is number 1 and the latest predictions say a Category 3 direct hit on Miami would turn it into "Atlantis." Ironically, New Orleans is "only" ranked fifth. Sylvester Giustino, BOMA/NY's Director of Legislative Affairs, says office building prevention and recovery costs from Sandy vary, but are well into the billions. Overall costs, including residential devastation, are second only to Katrina. And as Giustino stated at the BOMA/NY traveling seminar on lessons learned from Sandy, "It’s not a question of when New York takes a direct hit, it is when." Diving deeper into the knowledge base collected by our Lessons Learned task force members—who most recently spoke to a standing room only crowd at the BOMA International Conference—BOMAfacts learned the following about planning, preparing and recovering from these potentially devastating storms. Prepare for the 500-Year Event  John Brandstetter, a disaster recovery specialist who chairs our Preparedness Committee’s Weather Response Subcommittee and heads The Brandstetter Group, says "we must look beyond the 100-year to 500-year scenarios. Plans structured to handle 12 feet of surge didn’t hold up to Sandy--surge was 13 feet and often more in Lower Manhattan." (These scenarios are not calculated by time; they are percentage formulas applying to how often surge would meet or exceed past levels.) In the wake of Sandy, OEM and FEMA have redrawn the flood maps; the OEM map can be accessed at http://maps.nyc.gov/hurricane/. John Brandstetter, a disaster recovery specialist who chairs our Preparedness Committee’s Weather Response Subcommittee and heads The Brandstetter Group, says "we must look beyond the 100-year to 500-year scenarios. Plans structured to handle 12 feet of surge didn’t hold up to Sandy--surge was 13 feet and often more in Lower Manhattan." (These scenarios are not calculated by time; they are percentage formulas applying to how often surge would meet or exceed past levels.) In the wake of Sandy, OEM and FEMA have redrawn the flood maps; the OEM map can be accessed at http://maps.nyc.gov/hurricane/. Overall, Brandstetter says emergency and business continuity plans must go beyond withstanding the initial event to include recovery plans laying out all steps to be taken by all members of the building team, owner, tenants and vendors. "And go as deep into the details as you can," he reminds us. Such plans involve "taking a strategic view," added Walter Ulmer, III, who heads the emergency preparedness planning firm of Remlu, Inc., authored the Sandy task force report and moderates the panel. "They require that property managers take a broader view and prioritize recovery activities identified in advance, including specialized staff that will be needed. Make sure vendors are self-supporting in terms of personnel and supplies. Communication is essential; tenants must understand the minimum level of what’s needed to achieve operations, as well as the limitations—we have to be as effective getting back in as we are getting out." Why Insurance is Key—and Gets Overlooked With insurance policies often bought at the corporate level based on cost, Sandy’s havoc revealed more than just physical wreckage—some owners faced multi-million dollar repair bills exceeding insurance premiums by 500 percent or more. Brandstetter explains why. "Insurance coverage no longer reimburses dollar for dollar. Insurers now look at how you plan to mitigate flood disasters and base your premium on the steps you’ve taken. That must be communicated to whoever buys the insurance in your organization. Everyone from the property staff to the corporate financial team—and key tenants, if appropriate—must know your insurance coverage contract in and out," he continues. "If you didn’t do it after Sandy, do it now. Hold a meeting to review your insurance policies. Know what affects operations and the bottom line," he strongly advises. "Bring in a professional to explain the policies—millions of dollars and hundreds, perhaps thousands of man-hours and vendor costs are on the table. And should an event occur, keep a log and try to take digital photos to chronicle your story and build evidence for your claim." Lawsuits on Sandy-related insurance coverage are now being filed. In one case reported in July by The Wall Street Journal, an office building owner in Lower Manhattan has named both the insurer and the building’s managing company as a defendant--even more reason to know your policies inside and out. Operational Missteps  Successful preparation often lies in the details, as these anecdotes from Sandy revealed. (For more of our task force’s Lessons Learned advice, see the "Checklist" story in Committee Corner.) Successful preparation often lies in the details, as these anecdotes from Sandy revealed. (For more of our task force’s Lessons Learned advice, see the "Checklist" story in Committee Corner.) • Buildings with garages had not tested their doors in years; when rolled down, they were found to be in poor condition. Storm surge would have ripped them off their hinges; test these as part of your emergency prep • Email and telecommunications blew out; consider using the cloud system • Since communications will be hectic before, during and after the storm, bring in crisis communications personnel during original communications planning so all critical emails/phone numbers are obtained in advance • Oil tanks were not heavy enough to remain in their concrete settings during the storm; use metal straps to keep in place • Many placed their emergency generator fuel supply in a potential flood area—harden the area if it cannot be moved, a step that may also lower insurance costs "Don’t wait until you hear a ferocious storm is brewing off Florida to pull your plan off the shelf. Do it now. Your plan is a living plan; rehearse it, drill it, update it, then meet with the other groups involved from owners to vendors so their roles are clearly understood. Decide your risk tolerance; each company is different," says Brandstetter. "Risk has to be mitigated and chaos managed. A strong, comprehensive plan gives you a solid foundation to hang on to during the biggest cost-incurring force your building will experience—Mother Nature." And as the record books show, Mother Nature almost always wins. The Island That Disappeared  It used to be the summer playground of Tammany Hall, right off the Rockaways; a Belle Epoque forerunner of the Hamptons, where politicos and robber barons rubbed elbows on its beaches, and in its bathhouses and saloons. It was known as Hog Island, ironically, and this sandy retreat was very much in vogue from the Civil War until the night of Aug. 23, 1893, when a Category 2 hurricane roared into the swampy south coast of Queens where JFK International Airport is now located. It used to be the summer playground of Tammany Hall, right off the Rockaways; a Belle Epoque forerunner of the Hamptons, where politicos and robber barons rubbed elbows on its beaches, and in its bathhouses and saloons. It was known as Hog Island, ironically, and this sandy retreat was very much in vogue from the Civil War until the night of Aug. 23, 1893, when a Category 2 hurricane roared into the swampy south coast of Queens where JFK International Airport is now located. Called the "West Indian monster" by New York City's tabloids and legitimate press, the hurricane and its 100-mile-an-hour winds drove a wall of water 30 feet high across the borough and southern Brooklyn, destroying most man-made structures and uprooting thousands of trees. Central Park was defoliated as trees were ripped out by their roots, dozens of boats were lost and the papers reported that "scores of sailors" drowned. The Met Life building on lower Madison, which had just recently opened, was badly damaged. But Hog Island was completely destroyed. To this day it holds the distinction—which one would expect to be conferred on a tropical isle in the hurricane-fertile Caribbean—of being the only island on this planet removed from existence by a hurricane. |

| BOMA/NY Suite 2201 Eleven Penn Plaza, New York, NY 10001 Ph: 212-239-3662 Fax: 212-268-7441 www.bomany.org |

|