Time to Take a Step Back and Evaluate Moving Forward

![]() Print this Article | Send to Colleague

Print this Article | Send to Colleague

GMIS RFC 001

By Marc Thorson

Assistant Director of Information Technology

Village of Schaumburg, Illinois

P: 847-923-3806

Disclaimer: This article is meant for thought and discussion purposes. This is my own opinion and work, and does not reflect the views of my employer. Please let me know your thoughts on this article. I can use all the constructive criticism I can get.

Executive Summary

This article is a request for discussion of sorts. Information technology is advancing quickly. Unfortunately, in many instances the advancements are implemented too quickly for research or measurables to determine if the technology is working.

The example used in this article is mobile data computers (MDCs) in police squad cars. Any research I was able to find did little in justifying the MDCs improving policing strategy or outcomes. Yet we continue to expense upwards of $4,000 per squad car to outlay these devices without ever knowing if they help the officers improve their ability to serve and protect the community, or if they are actually a detriment. While there may be a need for technology in the squad cars or physically on the officers, are we heading down the correct path with full-fledged computers mounted in an already cramped vehicle? To answer this, we must begin asking specific, pointed questions to determine objectives on technology requests. We need to determine how to quantify if we are meeting those objectives. We need to train users on not just how to use the technology, but how to use the technology to improve their work. And finally, we need to share the resulting data to determine overall effectiveness of the technology. If these things can be accomplished, we will not only see improved effectiveness of our customers, but it will also work to improve the level of technology provided by our vendors. Contrarily, continuing down this path where innovation outpaces maturity and accountability can be detrimental to our industry.

Background

Information technology has a bad habit. Our industry direction is changing faster than it is maturing. It is not completely our fault; it is the nature of the business. If we are not innovating, we feel we are losing value and leverage. It is, to a point, expected by the organization that we continue to push the proverbial envelope. Every day we are being asked, either directly or indirectly, "What have you done for me lately?"

I was recently at the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) Law Enforcement Information Management (LEIM) conference. This conference is dedicated to the information and technology side of law enforcement. I heard many great speakers and collected excellent information. There were three concepts I took from that conference which I felt were game changers. Given that this was a law enforcement conference, the topic of this article is very police-centric. However, these ideas can be taken and used with any department or business unit.

The first idea is not to be hesitant to ask questions about the technology we have and are evaluating. We need to know exactly what we are accomplishing. The second idea is to include more extensive training that dives deeper into what we are trying to accomplish with the technology. The third idea is that grass roots initiatives work. We cannot wait for higher governmental bodies to provide us with our needs, sometimes we need to push forward ourselves.

Many of the systems we implement have all the promise in the world, but are they working properly and achieving the desired result? For instance, how valuable to the police officers are squad car mobile data computers (MDCs)? They are expensive (devices can be over $4,000 per vehicle between the device, mount, and installation), they take up a lot of space in an already cramped vehicle, they frequently break, and they can be a liability if officers are typing or reading while they drive. Reasons to implement MDCs can include reducing radio traffic and freeing up officers’ time (Lindsay, 2012, p. 306). Is radio traffic actually reduced? I could not find any answers through research for that question. I did find out that, since implementing terminals or computers in squad cars, statistically there are more searches of State and Federal databases, and the amount of time required for officers to complete reports has gone up (Ioimo, 2004, abstract). Are the computers in squad cars a positive factor or a detriment to what the Police department wants to achieve? Most importantly, how would we know?

Before going any further, I want to make it clear that I am not advocating removing technology from the equation. But, in speaking with colleagues and my own experiences, we easily find ourselves using technology to solve process problems, or technology seemingly for the sake of technology. If this situation happens too often, it can be a symptom of a larger problem of how IT is perceived in the organization. Is IT simply break/fix or are we a partner in the decision-making process? We can combat the former by working with our colleagues in the other business units and using strong strategy and governance ideas.

Research and Ideas

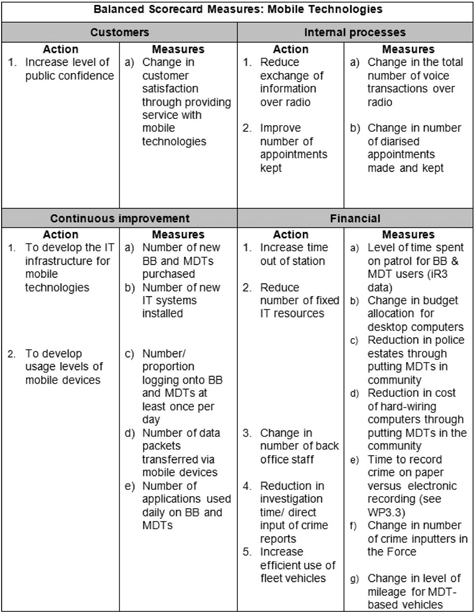

Planning and asking questions are ways to start. When investigating any new technology, strategy should guide governance, which in turn should guide projects. In IT, we should have a strategy that aligns with the overall organization’s strategy. This, in theory, would align with the police department’s strategy as well. The ideal method would be a holistic approach. One recommendation in my research is to pull historical statistics and conduct surveys on various attributes to create a balanced scorecard (Lindsay, 2012, p. 313). While this would be ideal, in many cases it may not be practical without resources and the complete support of the police department to carry out the research. However, I did attach a sample balanced scorecard for mobile technology as Appendix A for those interested.

In lieu of an all-encompassing scorecard, I am recommending focusing on objectives and metrics IT can control with the assistance of the police department. Using IT strategy as a guide, we need to develop protocols which govern the threshold for pursuing technology. This threshold is what can make our lives easier. We, as IT professionals, try hard not to be the "No" people, but this threshold gives us the power to say "No" without being the bad guy/girl. If done correctly, the customer sees where the issues are, and will say "No" themselves. All the while being able to justify the decision to anyone asking.

To determine this threshold, one should begin by asking the customer questions such as, "What organizational or department goal will this project impact?" In my experience, this question becomes difficult to answer if the project is due to a mandate from the state or some higher governmental agency. If that question does not work due to regulation, try others such as, "What aspect of your operations do you anticipate improving by implementing this?" Chances are there is some valid reason for the regulation, and this would be a great opportunity to track if the project truly accomplishes its intended purpose. Make sure the answers are as specific as possible.

In my organization, we have developed a form which needs to be completed which asks these questions along with others such as identifying cost savings and requires a department head signature. If the form is chosen, make sure the executives of the organization support the initiative to keep it from being circumvented. I believe, more often than not, organizational leaders like seeing these types of controls in place as it helps them do their job better.

At this point, there will be clear objectives for the project. The next task is to determine how those objectives are met. Metrics are quantifiable components used to measure a project’s performance (Rouse, 2007). Metrics should be specific, measurable, relevant, and time-bound. One should determine specifically what relevant data can be used to measure the achievement of a product or service over a pre-determined period of time. This could be objective data tracked by systems already in place, subjective data such as through employee surveys and observations, or a combination of both. Choose whatever makes sense for the situation and the level of resources available, and make sure this is set prior to evaluating products. These objectives and measurables can be hashed out in one or two meetings, and the more often you gather this information the chances increase your customers will have these answers ready to go at the onset of a new project.

In addition to governance and metrics, it is important to determine training requirements. In a study in the Policing section in the Oxford Journal, over half of officers felt technology did not make them more productive (Koper, 2014, p. 216). For example, the agencies studied were asked how technology was used by the officers. The study showed consistently that the majority of officers used technology for traditional, reactive policing activities such as checking the call history for a location, and less than 50% used technology for proactive strategies such as determining patrol locations ("indicative of hot spots policing") or "how to respond to a crime problem (indicative of problem-orientated policing)" (Koper, 2014, 217). In far too many cases in the initial evaluation of a product, everyone involved has great ideas for how to use the technology for better outcomes. Unfortunately, many times those ideas never filter down to the people using the product (Koper, 2014, p. 217). A way to combat this issue is to determine two levels of training at the onset of any evaluation. The first training is how to use the product, and the second is how to use the product to achieve the department’s goals. This second training has a direct impact on any metrics created, so it is critical to include it.

Please note that if these ideas are significantly different than the typical practice in your organization, this is not all or nothing. It has been my experience that culture can prohibit radical and wholesale changes. So, implement good change management strategies, such as a slower, phased approach, which will lessen the resistance to acceptance. Any of these ideas can make a positive impact on IT and organization operations.

Finally, there is a definite need to be able to share the results of the metrics in an anonymous, aggregated fashion. Perhaps, using GMIS International as a clearinghouse, those metrics can be built into large enough samples to draw complete conclusions. This is where a grass roots plan can develop into actionable information. I believe the GMIS International Big Data initiative would be very beneficial. The difficulty would be normalizing the data for this initiative. Twenty different organizations can agree on the same project using the same vendor, and could potentially have twenty different objectives and outcomes. Until this work is ubiquitous across agencies, we cannot begin to start developing standards, which would make starting this project a very manual process.

What else can be done?

ARJIS stands for the Automated Regional Justice Information Systems. This organization resides in southern California, and provides systems and information sharing for more than eighty organizations in the San Diego area. At the LEIM conference, they provided a session in which they engaged the services of RAND Corporation to investigate the effectiveness of technology that was in place. This was a touchstone moment which confirmed what was suspected. Very little research has gone into the effectiveness of law enforcement technology (Mugg, 2015).

This project, which focused on one specific officer notification technology, was thoroughly researched using historical research on specific criteria. Using a scientific method, they analyzed control data from a time period prior to the existence of the technology and then measured it against data obtained after the implementation of the technology. They also accounted for possible reasons the technology was not used when it was available. I was not able to take pictures of the slides as we were given an advanced look into the work prior to its being published. However, I can tell you in this instance the data supported the use of the technology.

As an organization, it may be beneficial for GMIS International to partner with a university or research company in coordinating future technology in law enforcement and other public sector technology studies. Similar to what ARJIS has accomplished with Rand Corporation, further work can be done to help public sector agencies in determining what technology works, and what does not. Studies can be distributed to members to arm them with useful information when making decisions.

The information gathered for these studies would also create a ripple effect to help companies in the law enforcement technology field. Currently, there are very few standards which cause police technology to vary greatly from one vendor to the next. As an educated consumer, we can effectively vote for standards with our money when enough of us have that information at our disposal.

Conclusion

Currently, there is a severe lack of information regarding how effective current technology is in law enforcement and other public sector fields. This does not mean we should not pursue technology, but rather we need to make a concerted effort to determine effectiveness and hone in on technology that works and makes sense. Where do we start? By asking pointed, purposeful questions and setting objectives. By determining how to measure success. By starting at a grass roots level, tracking the metrics, and sharing the results. Otherwise, this constant push forward with little regard to research and measurement can have a detrimental effect on our industry and craft. In other words, we need to take a step back and evaluate moving forward.

Sources

Ioimo, Ralph E., Aronson, Jay E. Police Field Mobile Computing: Applying the Theory of Task-Technology Fit. Police Quarterly. 2004. Volume 7, Number 4 403-428. Abstract

Koper, Christopher S., Lum, Cynthia, Willis, James J. Optimizing the Use of Technology in Policing: Results and Implications from a Multi-Site Study of the Social, Organizational, and Behavioural Aspects of Implementing Police Technologies. Oxford Journals: Policing. 2014. Volume 8, Number 2. Pages 212-221.

Lindsay, Dr. Rachael, Jackson, Dr. Thomas, Cooke, Dr. Louise. Assessing the Business Value of Mobile Terminals in a UK Police Context. The Police Journal. 2012. Volume 85. Pages 301-318.

Mugg, Katie, Herberman, Erinn, Jackson, Brian, Kovalchik, Stephanie. Meaningful Metrics: Tips for Ensuring a Successful Technology Evaluation. International Association of Chiefs of Police Law Enforcement Information Management Conference. Conference, May 19, 2015.

Rouse, Margaret. Business Metric. Whatis.com. March 2007. http://searchcrm.techtarget.com/definition/business-metric

Appendix A

(Lindsay, 2012, p. 313)

*Please Note: BB = Blackberry Device

Thank you to the following people who helped edit and proofread this article:

Brian Johanpeter

Director of IT

City of Mattoon, Illinois

Glen Liljeberg

Director of IT

City of Westmont, Illinois

Peter Schaak

Director of IT

Village of Schaumburg, Illinois