INVESTING

Markets Don’t Care about Your Politics … but Clients May

By Michael Costa

There’s a lot of angst out there in America, and it’s hard to blame anyone for feeling deep distress. Data shows that polarization has reached all-time highs, and trust in government is hovering near all-time lows. Society feels increasingly fractious and tribal.1

While professionals of all types often assume they should check their politics at the door, financial advisors frequently find their clients feel differently. Increasingly, clients bring their politics into conversations about markets and portfolios. Perhaps this shouldn’t come as a surprise. Relationships require trust, and what better way to establish trust than to confirm you’re both members of the same “team.”

Whatever the underlying driver, this tendency poses some interesting challenges. Clients may want to reduce risk in a knee-jerk fashion when their party loses an election, but their actions could actually raise their risk of not achieving their long-term investment goals. More common are requests to exclude certain sectors or companies from portfolios. We’ve seen these requests rise markedly in the last two decades as activists have encouraged the public to “protest with their money.”

The most common response from advisors is to sidestep political conversations and accommodate those with strong views through tweaks to the portfolio. Another approach is to overtly embrace one political/social outlook or another as an effective form of niching—provided you’re being true to your convictions. This has long been embodied by ESG-oriented firms and, less commonly, by firms with a client base in deep red states or conservative Christian communities.

A third, perhaps less common response is to gently push back, using evidence to explain why values are important, but politics are best left at the voting booth. If that’s a fit for you, here are two key arguments you can use.

Reason 1: Politics Don’t Determine Market Outcomes

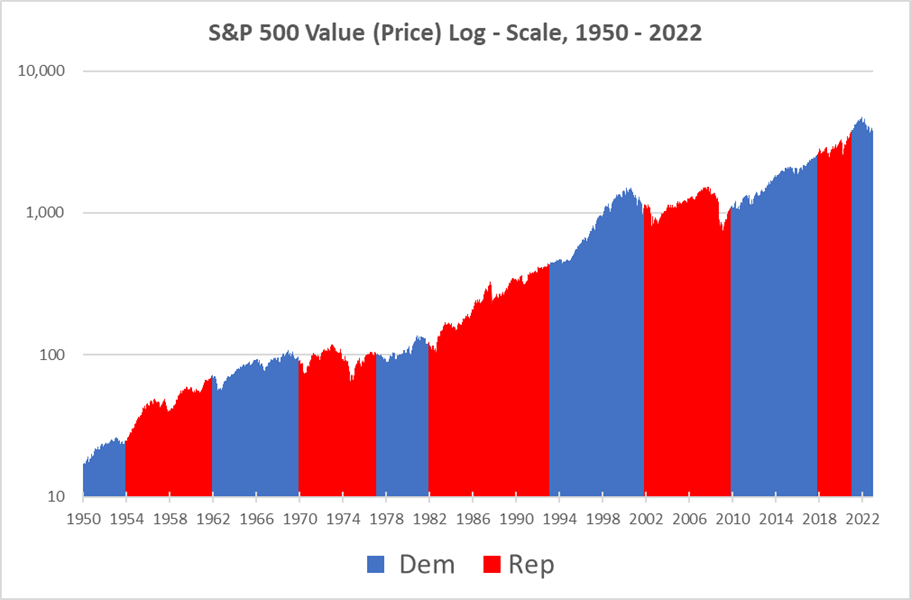

The stock market is relatively indifferent to which party is in power. Historically, the S&P 500 has performed slightly better during Democratic presidential terms than Republican terms. Looking at it through a congressional lens, the S&P has tended to do slightly better under Republican control than Democratic control, but best of all when Congress was split.2 But through it all, the stock market tends to continue to rise over time (see chart below), and most statisticians fail to find a meaningful relationship between the S&P and presidential election outcomes.

This lack of a clear link between politics and equity returns seems common, if not pervasive, among developed democracies. In 2017, Research Affiliates ran statistical studies on Canada, the U.K., Germany, Australia, and France and found no systematic relationship between the party in power and stock market returns in any of those equity markets.3

There are many possible reasons why the link between politics and markets is weak:

- Central banks have far more influence over the economy than the executive branch and legislature in the short run, and central banks tend to be fairly well insulated from politics.

- Government spending (fiscal policy) certainly does influence economic growth and, therefore, markets, but the impact tends to be realized with a lag that’s sometimes measured in years. The impact may not fully coincide with the term of the decision-makers most responsible for the policy.

- In the U.S., fiscal policy differences between the parties are actually not as large as imagined. Republicans and Democrats prioritize different types of spending and levels of taxation, but both parties tend to stimulate the economy via budget deficits.

- Domestic policymaking isn’t the only (or even the main) driver of long-term growth in the economy. Factors like population growth, innovation, capital investment, and even economic activity outside the U.S. are all important. None of these are directly controlled by our politicians.

Reason 2: Constraining Portfolios May Harm Performance

When right-leaning investors decide to avoid China, BlackRock products, gaming stocks, or certain healthcare companies, they do themselves no favors. The same is true when left-leaning investors exclude oil, defense, and mining stocks. A significant number of investors (notably in the ESG space) have been convinced that systematically excluding certain types of investable assets from portfolios on criteria other than expected return is a good way to improve performance over time. However, there is simply no real basis for that view.

From a theoretical perspective, the ability to choose always has a positive value. Fewer options and greater constraints are never in themselves additive to results, except to the extent that they may constrain incompetent management.4 If incompetence is the threat, then seeking additional expertise or going static and passive is the correct response, not semi-arbitrary sector exclusion. Excluding wide swaths of the market limits diversification potential and hampers the advisor’s ability to pivot in times of need. In extreme cases, it can encourage crowding into expensive or otherwise unattractive assets.

2022 was instructive. ESG investment strategies tend to have a structural overweight to tech stocks and permanent underweights to nonrenewable resources, industrials, mining, and defense stocks. As a side effect, they also tend to be long “earnings duration” and growth style factors.

This didn’t turn out badly in the 2010s, as tech boomed and the oil-and-gas sector was the worst performer for the decade. But market patterns do not repeat forever. ESG equity strategies entered 2022 primed to lose money and with little room to maneuver. The fact that valuations for tech stocks have long been “stretched” only added to the pain. Even small holdings in the verboten sectors could have eased trauma, but unfortunately, that’s now water under the bridge.

Final Thoughts

There is nothing wrong with expressing oneself through a portfolio. Where clients have well-thought-out and sincerely held views about what types of economic activity are most desirable for society, advisors should try to accommodate them. And wearing your values on your sleeve seems to be a successful marketing or niching strategy for firms in many industries. There’s no reason to think the financial advice business is an exception.

Still, the reality is that most clients overestimate the importance of politics in market performance and do not have a clear view of how eliminating investment options can affect their portfolio outcomes. Where the client relationship is sufficiently close, acknowledging the client’s concerns and gently pushing back on politically motivated decision-making can be a viable option.

1. Laura Paisley, “Political polarization at its worst since the Civil War,” USC News (Nov. 8, 2016).

2. LPL Financial via LPLresearch.com, “2 Post-Election Charts You Need to see,” 11/4/2022. Based on S&P 500 Index 1950-2019.

3. Research Affiliates, “Presidential Politics and Stock Returns: Is the Relation Real or Spurious?” R. Arnott, B. Cornell, V. Kalesnik, 6/2017.

4. “Virtue is Its Own Reward: Or, One Man’s Ceiling Is Another Man’s Floor,” Cliff Asness, AQR, 5/18/2017.

Michael Costa, CFA, CFP®, is the chief investment officer of NextStep Portfolios, a firm dedicated to helping fiduciary financial planners build and manage institutional-quality investment portfolios for their clients.

image credit: istock.com/enjoynz