Canada’s Mills Challenged to Produce More Than Just Pulp and Paper

According to a report published this past week by The Globe and Mail, Toronto, Canada, many pulp mills and towns in the nation are struggling to rise from the ashes to fit the demand of new forest related products. Already In the case of Kitimat and several other former mill towns in British Columbia—such as Campbell River, Prince Rupert and Squamish—investors are proposing LNG (liquefied natural gas) facilities using some of the choice industrial and shipping sites left behind by the pulp and paper industry.

But other mill towns elsewhere in Canada don’t have such opportunities. They are looking for new ways to put their forests to use, as technology has increasingly made traditional paper products increasingly obsolete.

"It’s not easy to just bring a new industry in," said Bruce McIntyre, the head of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP’s Canadian forestry group in Vancouver. "You’ve got to go with the resources you’ve got."

And the resource Canada still has in abundance is forest – 348 million hectares of it, according to Natural Resources Canada. The industry is increasingly looking for ways to convert the wood fiber into a wide range of other products.

"Innovation is the engine of the future – maximizing the value of the fiber," said Catherine Cobden, EVP at the Forest Products Association of Canada.

Certain kinds of pulp are being used to manufacture absorbent materials for things like incontinence products (a growth industry due to aging demographics), to make synthetic fabrics, and even as binders in medicines. Lignin (essentially the "glue" that holds wood fibers together) is used in adhesives and animal feed. Sugars from the trees are being converted into biofuels. Sawdust and other waste materials are being compressed into wood pellets, which are increasingly popular in Europe and South Korea as a green source of fuel.

"Applications are far-ranging, from make-up, to food, to pharmaceutical needs," added Mark Martinez, director of the Pulp and Paper Center at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

An asset that former mill communities have going for them is a skilled labor force, left from a forest-product manufacturing process that has become highly technology-intensive over the years.

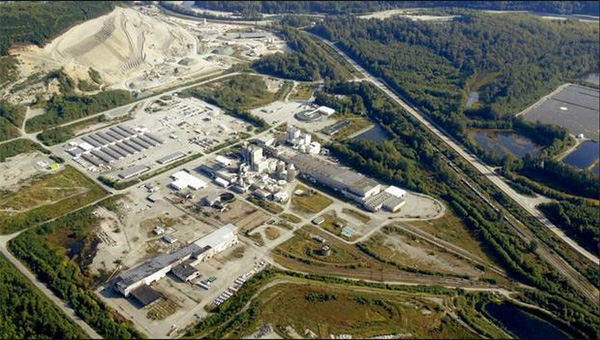

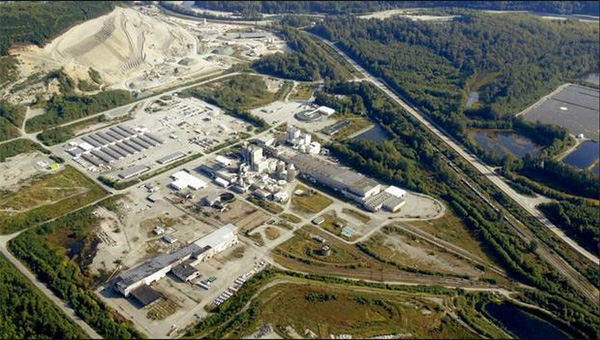

In Miramichi, N.B., a once-thriving forest products center whose pulp and paper mill closed in 2007, the town embraced a novel approach to keep workers connected to the community while it awaited new investment in its forest sector, notably a wood pellet facility proposed for its old mill site. Many skilled workers are continuing to commute to and from Alberta’s oil sands—working two or three weeks straight and then flying back to Miramichi for a week off. The municipality even expanded its airport so that direct flights could come in. It effectively keeps families together and brings some money into the community.

"It’s not ideal," said Jeff MacTavish, director of Economic Development for the City of Miramichi. "But the alternative was that they just pack up and leave."

Though new alternative businesses are finally being established in the mills, job opportunities do often pale in comparison to what they formerly offered. Miramichi’s pulp and paper mill, for example, once employed more than 1,000 people during peak operation years. The proposed wood pellet plant that would occupy the same site would employ about 100. In Brooklyn, N.S., a former pulp and newsprint facility that once had nearly 450 workers during peak operation is now being used by a pilot project for making diesel fuel out of wood fiber, which, if it’s successful, would have about 30 employees permanently on staff. Future projects will likely employ more workers on similar sites depending on the success of the Brooklyn pilot project.

Some of the employment availability issues for pulp and paper industry workers are the same for those working in other industries that do not have the declining demand pulp industry producers have been facing with certain paper products (such as newsprint which is becoming functionally obsolete for new generations of North Americans). Automated processes and new technology have eliminated the need for many industries besides P&P to perform under former peak job numbers. So for many Canadian residents and managers, they are happy the mills will continue to stay in operation with a solid plan for meeting future demand.

The Forest Products Association of Canada pointed out that the markets for these new alternative forest products "are quite competitive," with a much narrower customer base in many cases than traditional forest products. It will be a new race to capture market share in these innovative product sectors. There’s no guarantee that the Canadian industry will have a strong position.

TAPPI

http://www.tappi.org/