Engineered Softwood Could Transform Pulp, Paper and Biofuel Industries

According to a recent report from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wis., USA, scientists and researchers there have demonstrated the potential for softwoods to process more easily into pulp and paper if engineered to incorporate a key feature of hardwoods. The finding, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could improve the economics of the pulp, paper, and biofuels industries and reduce those industries' environmental impact.

"What we've shown is that it's possible to pair some of the most economically desirable traits of each wood type," says John Ralph, the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center's (GLBRC) plants leader and a University of Wisconsin–Madison professor of biochemistry.

According to Ralph, altering what once was the hard and fast distinction between softwoods and hardwoods — which process into largely separate product streams — could create opportunities for the multi-billion dollar industries that process biomass for profit.

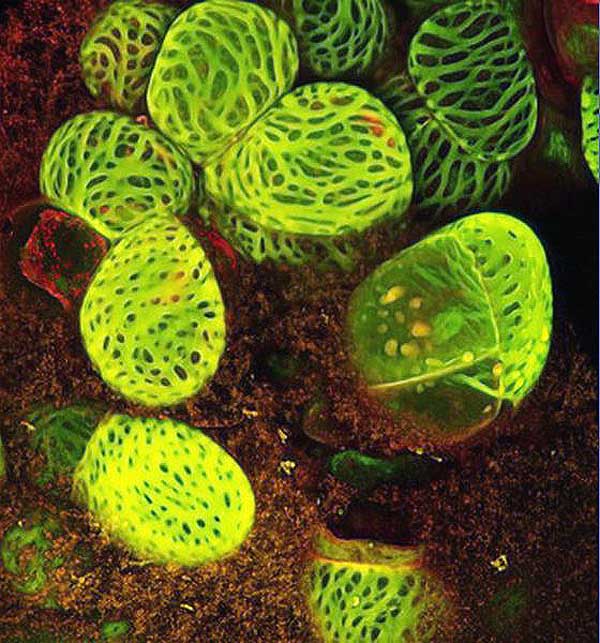

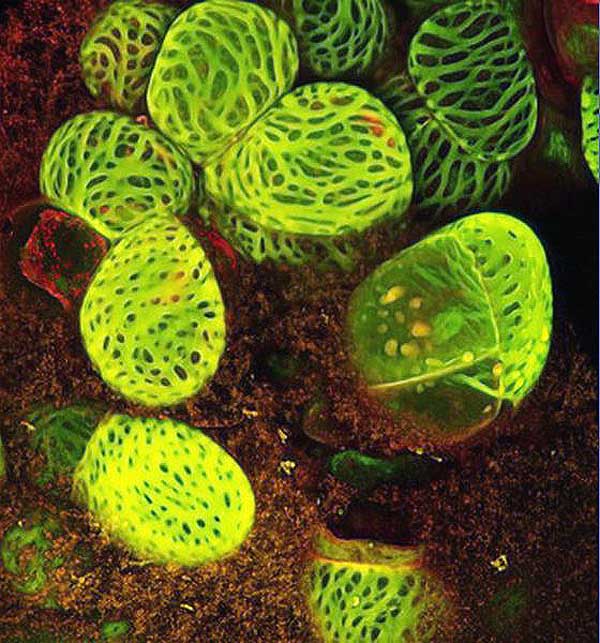

Photo: Softwood pine tracheary elements (TEs) from cells engineered to produce hardwood-type lignin. Photo: Lloyd Donaldson, Scion, New Zealand, and Matt Wisniewski, GLBRC

Like most plants, hardwood trees such as birch or poplar contain lignin, the notoriously hard-to-process "glue" that lends plant tissues their structure and sturdiness. Lignin is derived from binding molecules called G- and S-monomers, with S-monomers producing a simpler and more easily degradable lignin. As hardwoods contain both G- and S-monomers, they have traditionally been prized for their relatively easy processing into pulp or paper.

Softwoods such as pine or spruce, on the other hand, derive their lignin from G-monomers only, producing a lignin that is much harder to degrade and which renders softwoods more difficult to process. Their industrial advantage, however, is their long fibers, which are particularly well suited for use in making strong paper products such as shipping containers and grocery bags. In addition, the sugar found within softwoods converts more easily and in higher volume to ethanol, making softwoods a potentially superior feedstock for biofuels.

Ralph and a team of collaborators, including first author Armin Wagner from Scion, one of New Zealand's Crown Research Institutes, and GLBRC's Fachuang Lu, used a model called the "tracheary element" (TE) system to prove that it's possible to engineer conventionally long-fibered softwoods to contain the easier-to-process lignin found in hardwoods.

The TE system induces suspension-cultured cells to make secondary cell walls representative of those found in real wood fibers. In this study, the researchers transformed cells from softwood pine within the TE system by introducing genes for two key enzymes known to produce lignin in flowering plants, showing that the resulting softwood was capable of making and incorporating the S-monomers needed to produce a hardwood-type lignin in its cell wall.

Next, the researchers will attempt to use the same approaches to engineer actual softwood plants to produce S-monomers and S/G lignins. The transition from model to plant is highly anticipated.

"If we could implement this in real plantation softwoods, we could decrease the intensity of pre-treatment processes and increase yields across a variety of industries," Ralph says. "But there's a tangible environmental benefit as well: processing biomass faster and more efficiently cuts out a significant amount of waste and energy."

The research was funded partially by GLBRC, one of three Department of Energy Bioenergy Research Centers created to make transformational breakthroughs that will form the foundation of new cellulosic biofuels technology.

TAPPI

http://www.tappi.org/